All of our recommendations, unless specified, relate to acute COVID-19 in adults.

Some of our recommendations vary according to the severity of COVID-19 illness. Definitions of the categories are based on World Health Organization (WHO) criteria and can be viewed by clicking the plus (+) signs below.

RECOMMENDATION:

We recommend against use of Favipiravir in the treatment of mild, moderate, severe and critical categories of COVID-19 except in the context of a clinical trial.

DATE OF RECOMMENDATION: 19th July 2021

Definition of mild:

- Symptomatic (any acute COVID-19 related symptoms)

- AND respiratory rate <24/min

- WITHOUT pneumonia or hypoxia

Definition of moderate illness:

- Pneumonia (clinical or radiological) OR hypoxia (SpO2 <94% in adults with no underlying lung disease)

- AND respiratory rate ≤30/min

- AND SpO2 ≥90% on room air

Definition of Severe illness

Pneumonia with ANY ONE of the following:

- severe respiratory distress or respiratory rate >30/min

- SpO2 <90% on room air

- NO invasive or non-invasive respiratory support needed

Definition of critical:

- Requirement for high-level respiratory support: noninvasive ventilation, high-flow oxygen (≥20 litres per minute) or invasive mechanical ventilation

- OR acute respiratory distress syndrome (PaO2/FiO2 ratio of <300)

- OR sepsis

- OR shock

Favipiravir is an antiviral drug which has been evaluated in the past for treatment of Influenza and Ebola. Favipiravir was widely used in the initial part of the pandemic in Wuhan, Russia and many parts of Asia. It was initially used in India as well, after approval from Drugs Controller General of India in June 2020 and made its way into many state and institutional guidelines.

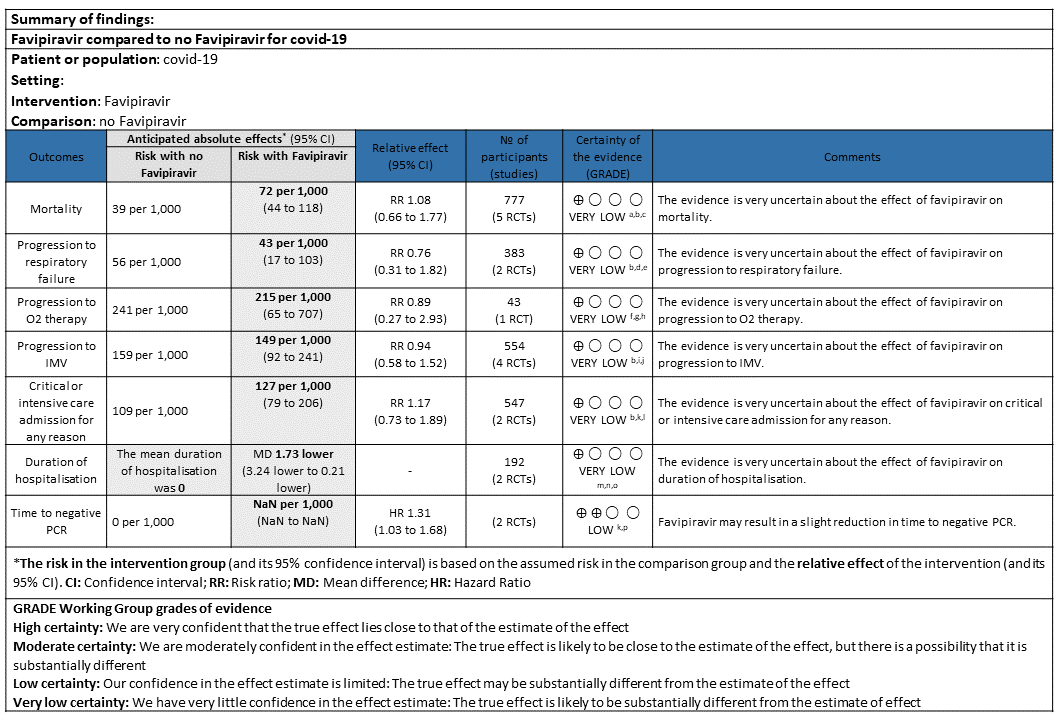

The evidence is low to very low certainty for all clinically relevant outcomes indicating that the effect of Favipiravir on all-cause mortality, progression to oxygen therapy, progression to invasive mechanical ventilation, admission to critical care or duration of hospitalization is very uncertain. The evidence seems to suggest that Favipiravir probably results in reduction of time to achieve negative PCR.

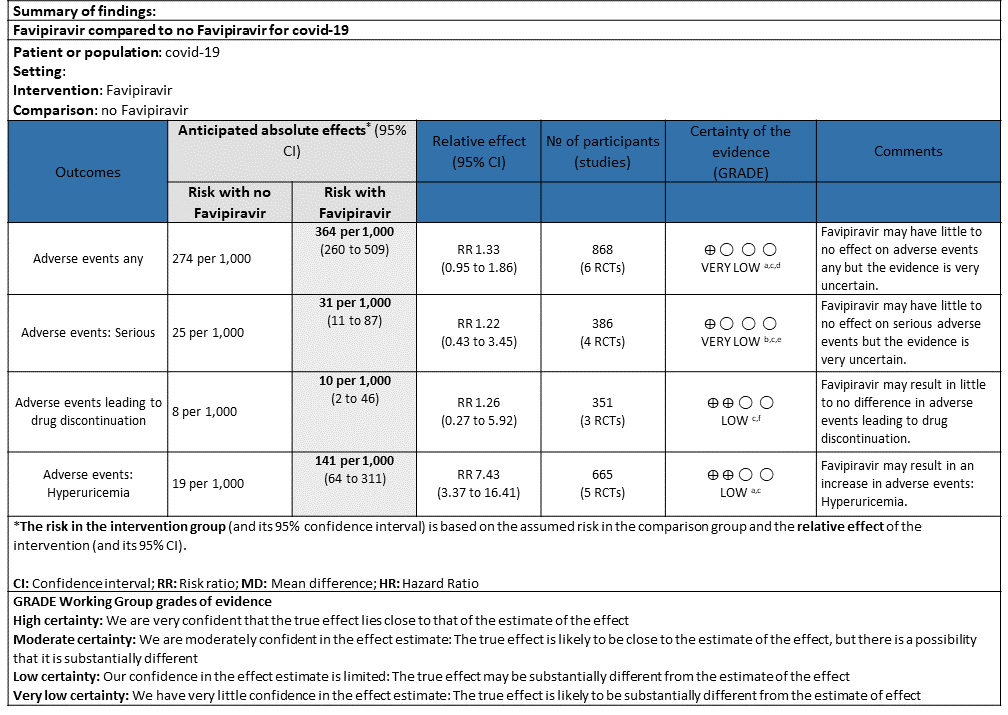

The evidence was very uncertain on adverse events and serious adverse events, but the effect estimates suggest an increase in hyperuricemia in arms receiving Favipiravir.

Overall, the benefit of Favipiravir in the treatment of COVID-19 is uncertain as there was significant heterogeneity among the trials, compared to what would be standard of care today and wide confidence intervals in effect estimates of critical outcomes. Hence at this point there is insufficient evidence to recommend this drug routinely in the context of covid-19.

Date of latest search: 16/6/2021

Date of completion & presentation to the Expert Working Group:16 June 2021

Date of planned review:16 December 2021

Evidence Synthesis Team: Hanna Alexander, Pritish Korula, Jisha Sara John, Naveena Gracelin, Bhagteshwar Singh, Priscilla Rupali

Explanations

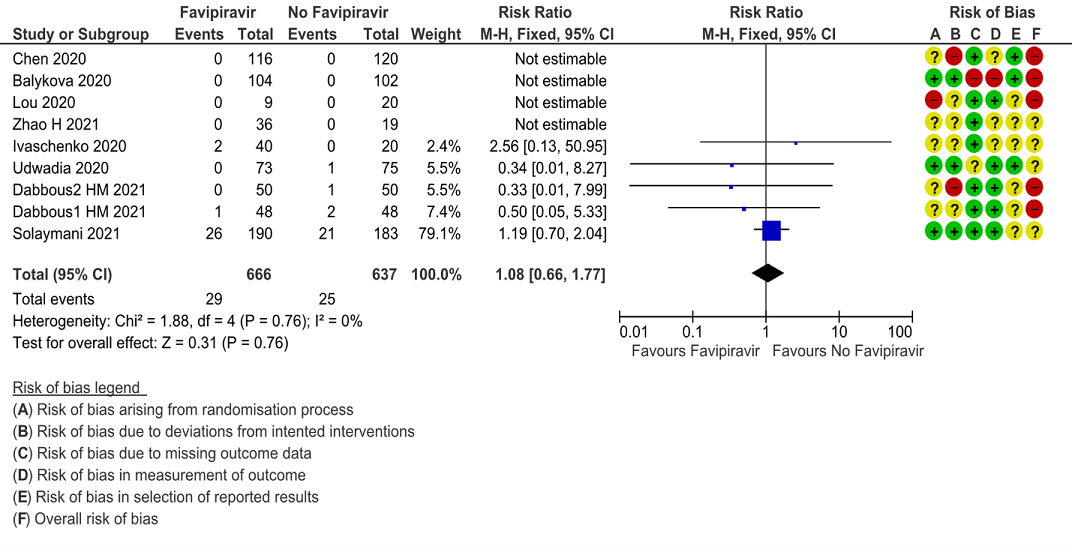

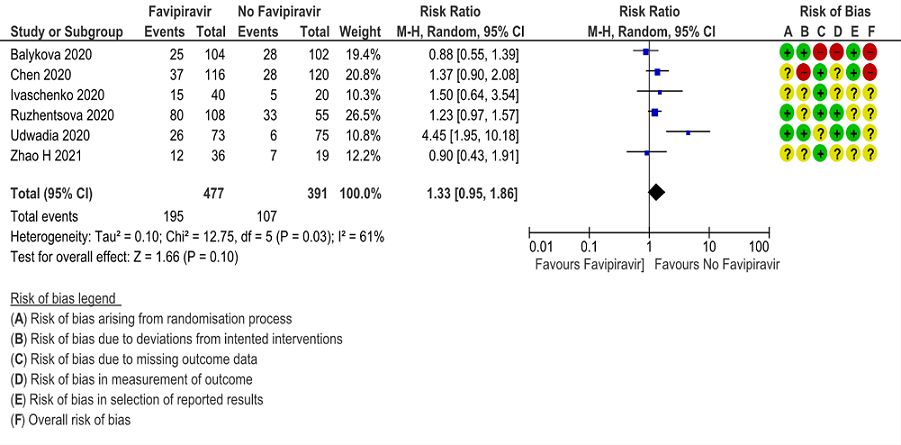

a. Downgraded by one level for serious RoB as the larger study with high events contributed to 80% weightage had some concerns

b. Downgraded by one level for serious indirectness as the severity of disease was different across the studies and different comparators used(SOC/placebo/active drug).

c. Downgraded by one level for serious imprecision as 95% CI crosses 1 (0.66 to 1.77). The RR pertains to 5 studies with events. 4 studies did not have events.

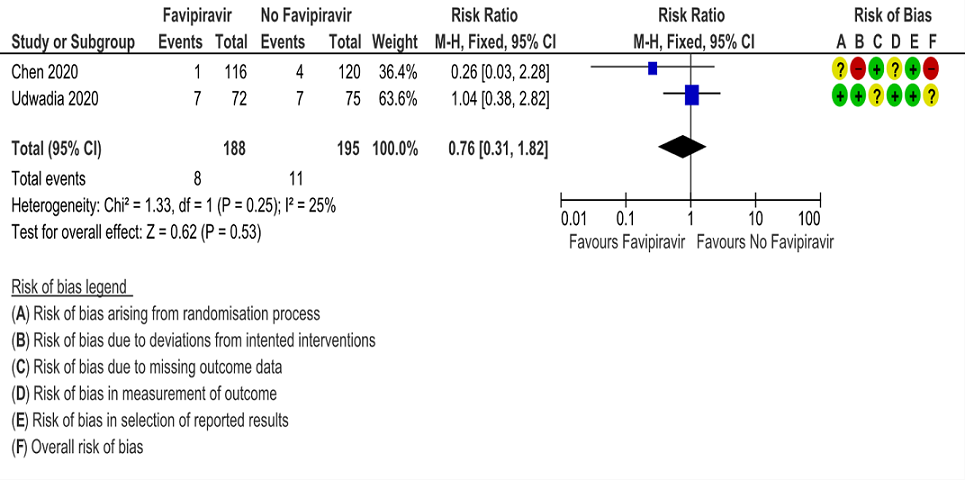

d. Downgraded by one level for serious RoB as Chen 2020 and Udwadia 2020 had high/ some concerns in RoB

e. Downgraded by one level for serious imprecision as 95% CI crosses 1 (0.31 to 1.82)

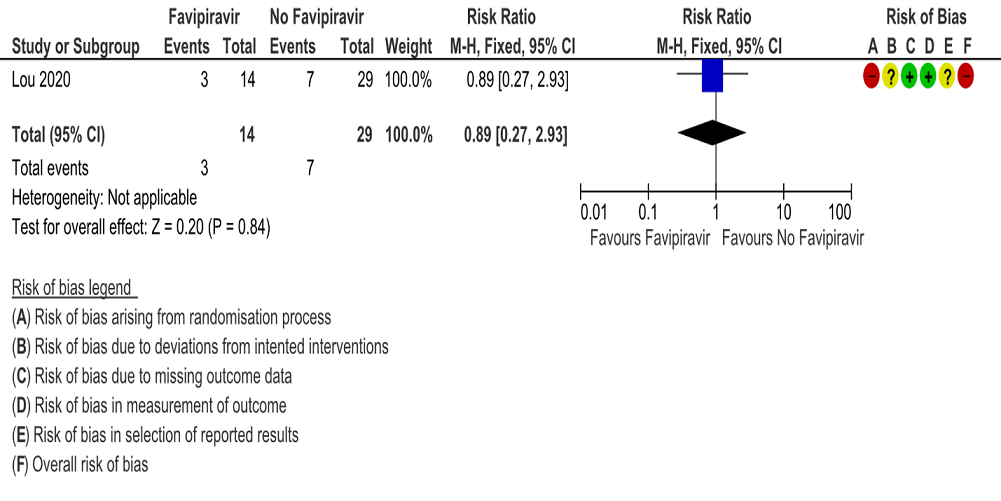

f. Downgraded by one level for high RoB

g. Downgraded by one level for serious indirectness as population had unclear severity in Lou 2020

h. Downgraded by one level for serious imprecision as 95%CI (0.27 to 2.93)

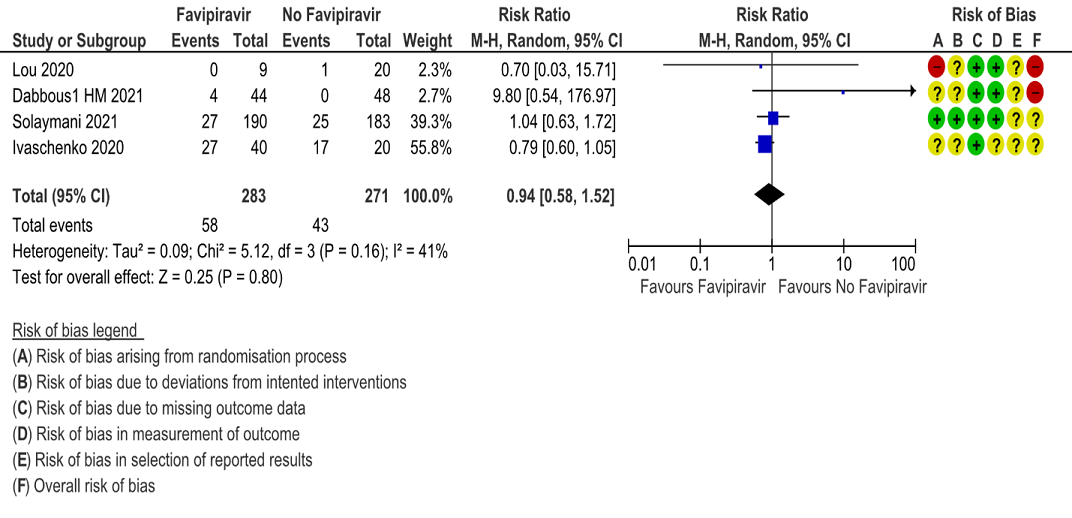

i. Downgraded by one level for serious RoB as two studies that contributed to the 90% of weightage to the results had some concerns for RoB

j. Downgraded by one level for serious imprecision as 95% CI crosses 1 (0.58 to 1.52)

k. Downgraded by one level as both studies had some concerns for RoB

l. Downgraded by one level for serious imprecision as 95% CI crosses 1 (0.73 to 1.89)

m. Downgraded by two-level for very serious RoB as both studies has high RoB

n. Downgraded by one level for serious indirectness as the severity of disease was different across the studies

o. Downgraded by one level for serious imprecision as the decrease was 1.5 days lower but the 95%CI ranged from 0.27 to 3 days which is clinically not interpretable.

p. Downgraded by one level for serious imprecision as the absolute effect is 1 few per 1000 which is clinically insignificant.

Favipiravir (T-705) is a synthetic prodrug, first discovered while assessing the antiviral activity of chemical agents active against the influenza virus. Excellent bioavailability (∼94%), 54% protein binding, and a low volume of distribution (10–20 L). It reaches Cmax within 2 h after a single dose. Favipiravir has a short half-life (2.5–5 h) leading to rapid renal elimination in the hydroxylated form. It was first approved in Japan for the management of emerging pandemic influenza infections in 2014 and later used for Ebola. Favipiravir was first used against SARS-CoV-2 in Wuhan at the very epicenter of the pandemic (1). Shannon et al found that the SARS-CoV-2–RDRp complex is at least 10-fold more active than any other viral RdRp known(2). Favipiravir acts by inhibiting this viral RdRp enzyme, allowing insertion of Favipiravir into viral RNA while sparing human DNA. The optimal dose of Favipiravir is difficult to establish from the limited preclinical, in vitro data. For instance, the higher dosing of favipiravir used in Ebola was based on preclinical studies showing the target concentrations needed to inhibit the Ebola virus were higher than that in influenza(1). Wang et al. found that the high concentrations of Favipiravir were needed to inhibit SARS-CoV-2 infection in Vero cells. Thus, it is difficult to ascertain the basis on which the current dose of this drug has been established in SARS-CoV-2(3). Despite this uncertainty, the dose in clinical use in most countries, including India, is 1800 mg bid on day 1, followed by 800 mg bid on days 2–14. In June 2020, favipiravir received the DCGI approval in India for mild and moderate COVID-19 infections. On June 7th 2021 the health ministry removed the drug from covid-19 treatment guidelines, however many clinicians continue to use in mild to moderate COVID 19 infections. This review aims to provide a summary of the available evidence from randomized clinical trials of Favipiravir for treatment of COVID-19, for any duration, which could guide clinicians and researchers regarding the appropriate use of this drug in the future.

We searched PubMed, Epistemonikos, and the COVID‐19‐specific resource www.covid‐nma.com, for studies of any publication status and in any language. We also reviewed reference lists of systematic reviews and included studies. We performed all searches up to 16 June 2021.

We searched the above databases and found 45 records. After removing duplicates and excluding those that did not match our PICO question, one systematic review was selected and included for the analysis. The AMSTAR score for the systematic review was found to be of low quality of evidence. The systematic review selected had 8 RCTs and 1 non-RCT. The 8 RCTs were further screened and 3 were excluded as they did not match the PICO question. We also went ahead and searched for new RCTs and found further 5 new RCTs which were included in the analysis. Thus a total of 10 RCTs were included for meta-analysis.

We extracted data for the following outcomes, pre-defined by the Expert Working Group:

- Critical (primary for this review):

- Progression to:

- Oxygen therapy

- Ventilation: non-invasive or invasive

- Critical or Intensive care (any reason)

- Duration of hospitalisation

- Progression to:

- Important (secondary):

- Mortality (all-cause) – at 28-30 days, or in-hospital

- Time to clinical improvement

- Time to negative PCR for sars-cov-2

- Complications of COVID-19:

- Thrombotic events

- Pulmonary function/fibrosis

- Long covid/post-acute sequelae

- Secondary infections

- Adverse events:

- All and serious, hyperuricemia

Two reviewers independently assessed eligibility of search results using the online Rayyan tool. Data extraction was performed by one reviewer, and checked by another, using a piloted data extraction tool on Microsoft Word. Risk of bias (RoB) was assessed using the Cochrane RoB v2.0 tool, with review by a second reviewer and compared with covidnma database. If there was a difference in more than one domain it was assessed by a third independent author. We planned to use risk ratios (RR) for dichotomous outcomes and mean differences (MD) for continuous outcomes, with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We planned to meta-analyze if appropriate, i.e., if outcomes were measured and reported in a similar way for similar populations in each trial, using random-effects models with the assumption of substantial clinical heterogeneity (the appropriateness of which would be checked by the Methodology Committee), and the I2 test to calculate residual statistical heterogeneity, using Review Manager (RevMan) v5.4. We used GRADE methodology to make summary of findings tables on GradeProGDT.

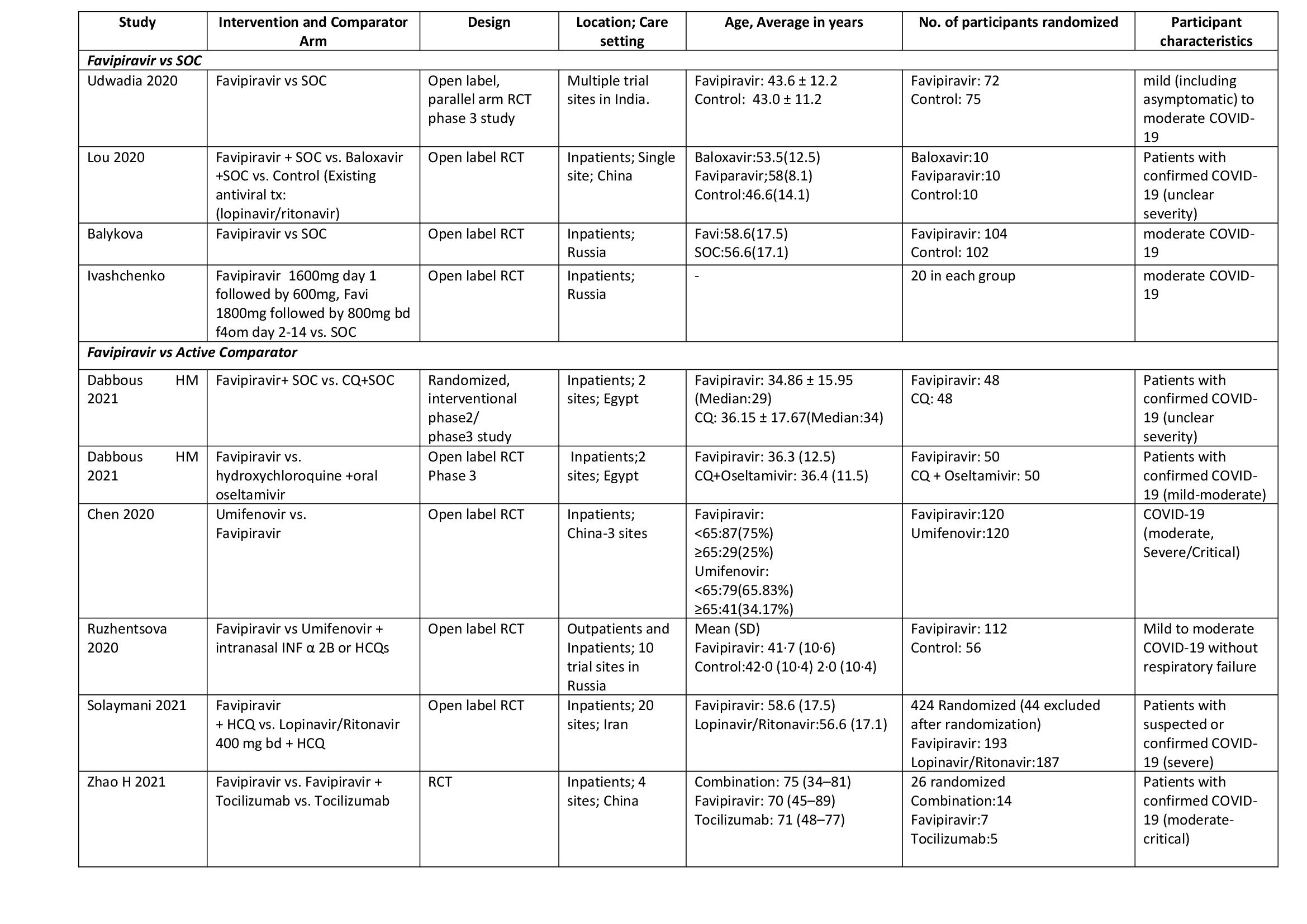

We found 10 RCTs that matched the PICO question as pre-defined by the expert working group. The trials included a total of 1494 participants, all of whom were adults. One trial reported from India(4), three each from China(5–7) and Russia(8–10), two from Egypt(11,12) and one from Iran(13) all of whom were of varying disease severity ranging from mild to critical. Also, the trials recruited participants to be enrolled to varying interventions. i.e. some studies compared Favipiravir with standard of care or placebo whereas others with active comparators. 8 trials (4–6, 8, 9, 11–13) were done purely on hospitalized patients where one study was done both inpatients and outpatients(10) and one study on outpatients alone(7).

Each trial and its results are described below; characteristics of the trials are summarised in the Summary of characteristics of included trials table. All the trials have varying risk of bias across all domains. Risk of bias for each domain per trial is displayed alongside the forest plots below.

The following comparisons were investigated in the trials (we compared outcomes for arms randomized to Favipiravir vs. standard of care or active comparators).

- Four trials(4,5,8,9) compared Favipiravir with standard of care(440 participants)

- Six trials(6,7,10–13) compared Favipiravir with an active comparator (e.g.: Chloroquine, Hydroxychloroqine+oseltamivir, Umifenovir, Umifenovir + Interferonα2B, Lopinavir/Ritonavir, Tocilizumab)

Since Favipiravir was compared with Standard of care, placebo and active comparators we did a sensitivity analysis to assess the robustness of the pooled estimate by stratifying the comparators separately from standard of care or placebo. We did this for critical outcomes of mortality, time to clinical improvement, time to negative PCR and duration of hospitalization. We concluded that there was no difference between the pooled estimate and the analysis done separately for Favipiravir vs SOC/placebo and Favipiravir vs Active comparator and hence decided to use the pooled estimate for representing the meta-analysis and summary of findings tables.

Our expert working group classified progression to oxygen, non-invasive ventilation (NIV) and invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) as critical outcomes and mortality, time to clinical improvement and thrombotic or secondary infections as important outcomes. However, as the situation in the country evolved, the guidelines group upgraded mortality, progression to respiratory failure, oxygen requirement and critical and intensive care admission as critical outcomes and others as important outcomes.

Critical (primary) Outcomes

As presented in the ‘Summary of findings’ table, the evidence is of low or very low certainty about the effect of Favipiravir on mortality, progression to non-invasive ventilation or high flow oxygen, progression to invasive mechanical ventilation, time to clinical recovery (not requiring oxygen or hospitalised care) and adverse events-all and serious, those leading to drug discontinuation or hyperuricemia. Whereas the summary of findings table represented the outcome, Time to negative PCR to have moderate quality evidence.

a. All-cause mortality: Very low certainty of evidence in 777 patients in five RCTs (4, 9, 11–13) found little or no difference between Favipiravir vs. standard of care or active comparator (RR 1.08; 95% CI 0.66 to 1.77). There were no significant differences observed even when trials were stratified by severity, risk of bias or comparators.

b. Progression to respiratory failure: Very Low certainty evidence in 383 patients from two RCT (4, 6), found that the evidence is uncertain about the effect of Favipiravir vs. standard of care or active comparator (RR 0.76; 95% CI 0.31 to 1.81).

c. Progression to oxygen therapy: Very low certainty evidence in 43 patients from one RCT (5), found that Favipiravir make little or no difference in progression to oxygen therapy when compared to standard of care or active comparator (RR 0.89; 95% CI 0.27 to 2.93).

d. Progression to Invasive mechanical ventilation: Very low certainty evidence in 554 patients from four RCTs (5, 9, 11, 13), found that Favipiravir makes little or no difference in progression to invasive mechanical ventilation when compared to standard of care or active comparator (RR 0.94; 95% CI 0.58 to 1.52).

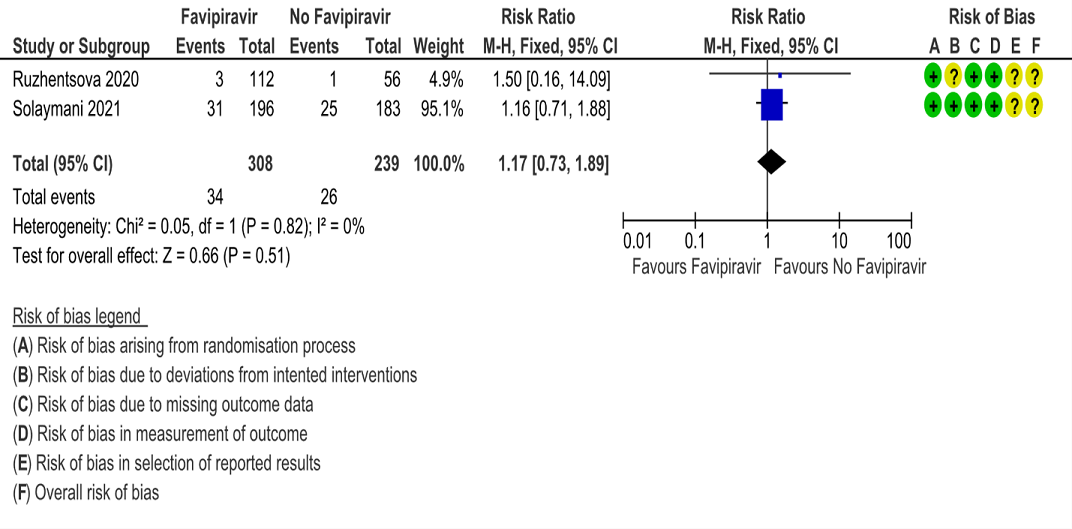

e. Progression to critical or intensive care for any reason: Low certainty evidence in 547 patients from two RCTs (10, 13), found that Favipiravir makes little or no difference in progression to invasive mechanical ventilation when compared to standard of care or active comparator (RR 1.17; 95% CI 0.73 to 1.89).

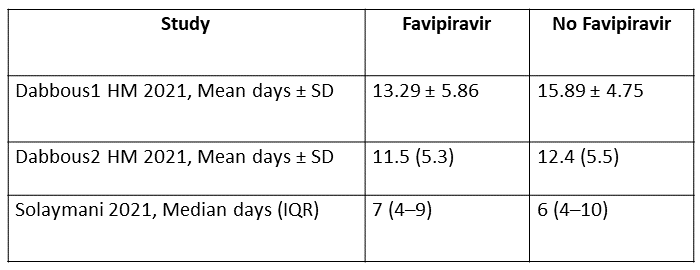

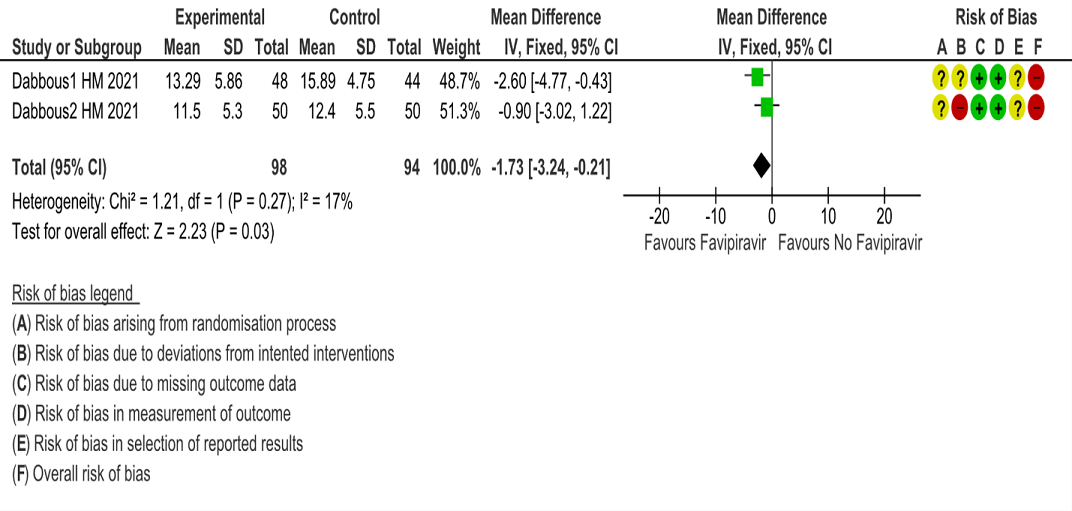

f. Duration of hospitalisation: Very low certainty of evidence in 192 patients from two RCTs (11, 12) that reported the mean duration of hospitalisation was 1.73 days lower in patients receiving Favipiravir when compared to standard of care or active comparator. One study reported a median interquartile range of 7(4-9) in Favipiravir vs. 6 (4–10) in the non Favipiravir group (13) which was not pooled with the other studies into the meta-analysis.

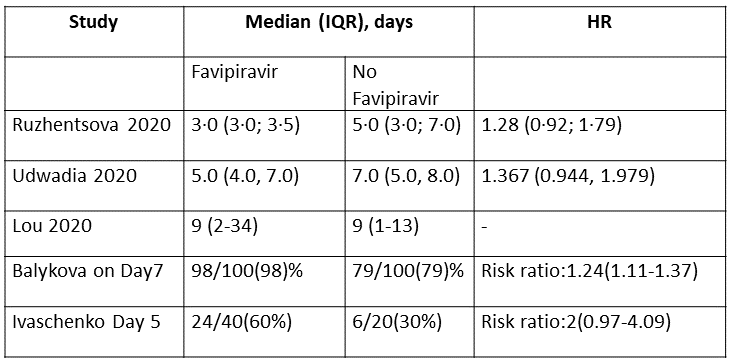

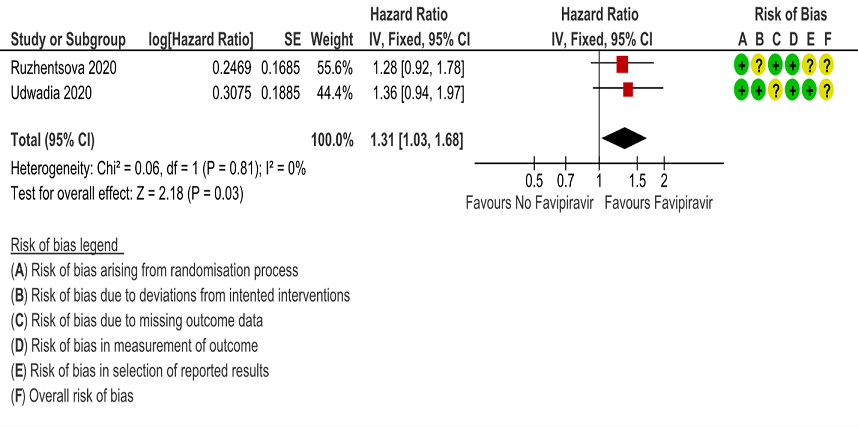

g. Time to negative PCR: Low certainty of evidence from 2 RCTs (4,10) found that Favipiravir may result in slight reduction in time to negative PCR when compared to standard of care or active comparator (HR 1.31; 95% CI 1.03 to 1.68). Two other RCTs (8,9) expressed the proportion of individuals becoming negative by PCR by day 5 and day 7 as 24/40(60%) for Favipiravir vs 6/20(30%) control and 98/100(98%) for Favipiravir and 79/100(79%) for control respectively.

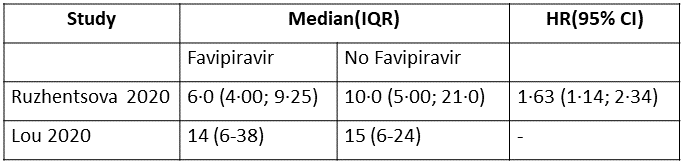

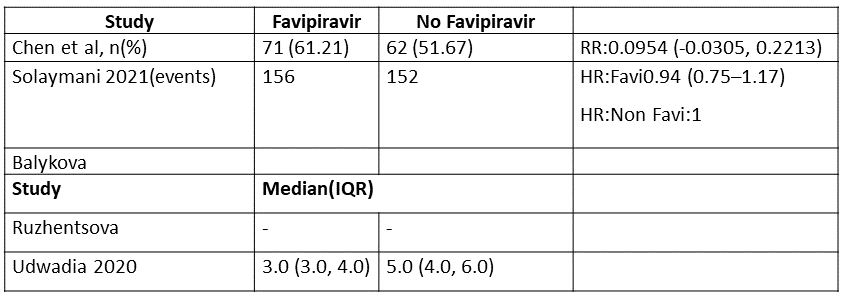

h. Time to clinical recovery (time to achieve WHO score 1,2,3 or not requiring hospitalization for oxygen or medical care): This was variably expressed in 3 trials and hence data could not be pooled. Proportion of people who recovered clinically in 1 trial (6,13) was greater in Favipiravir group as compared to the no Favipiravir group. In another study (4) this was expressed as median (IQR)and was found to be a median of 3.0(3.0-4.0) days in the Favipiravir group vs 5.0(4.0,6.0) in the control group

i. Time to clinical improvement (>2 point reduction in the WHO ordinal score): This was evaluated in 2 studies (5,10) and the time to clinical improvement was 6-9.25 days for Favipiravir and 5-21 days for standard of care or placebo. However, this data could not pooled as studies reported this outcome as median (IQR) and Hazard ratios.

j. Adverse events any: Very low certainty of evidence in 888 patients from 6 RCTs(4,6,7,8,9,10) found that Favipiravir may have little to no effect on adverse events any but the evidence is very uncertain when compared to standard of care or active comparator (RR 1.33; 95%CI 0.95 to 1.86).

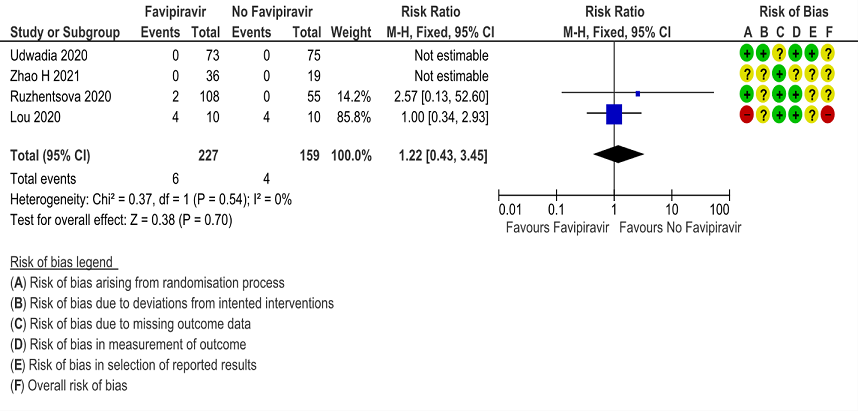

k. Adverse events Serious: Very low certainty of evidence in 386 patients from 4 RCTs(4,5,7,10) found that Favipiravir may have little to no effect on serious adverse events but the evidence is very uncertain when compared to standard of care or active comparator (RR 1.22; 95%CI 0.43 to 3.45).

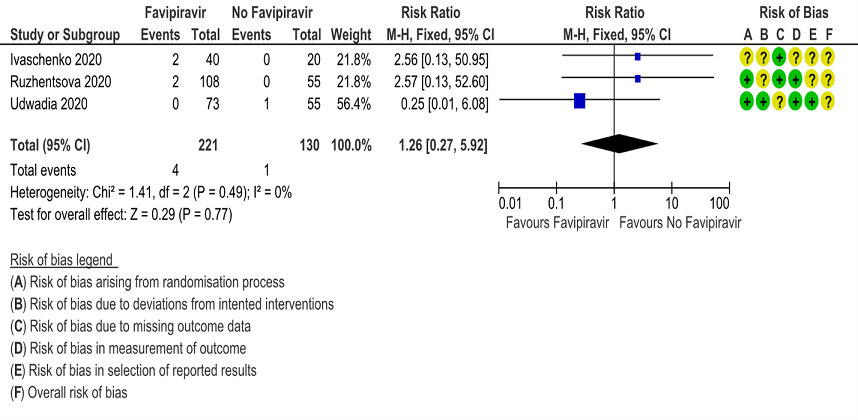

l. Adverse events leading to drug discontinuation: Low certainty of evidence in 351 patients from 3 RCTs(4,9,10) found that Favipiravir may have little to no effect on adverse events leading to drug discontinuation (RR 1.26; 95%CI 0.27 to 5.92).

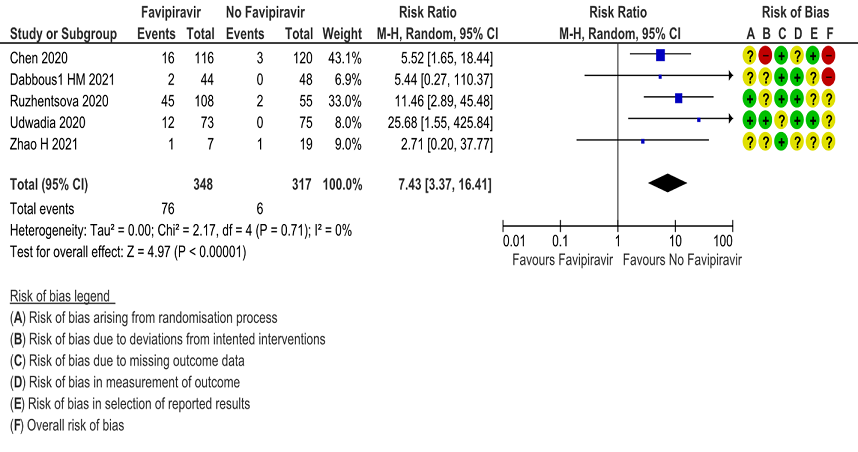

m. Adverse Events – Hyperuricemia: Low certainty of evidence in 665 patients from 5 RCTs(4,6,7,10,11) found that Favipiravir may result in an increase in hyperuricemia (RR 7.43; 95%CI 3.37 to 16.41).

Subgroup analysis

Disaggregated data could not be obtained for co-morbidities, inflammatory markers or different age groups. Subgroups of pregnancy, lactation, renal failure, liver failure were excluded from most trials. No data were available separately for immunocompromised individuals in any of the trials.

We also evaluated as per category of severity i.e., mild to moderate, moderate, severe and critical.

Mild-Moderate: Mortality [RR= 0.34(95% CI 0.04-3.20)]; Progression to respiratory failure [RR=1.04(95% CI 0.38-2.82)]; Critical or intensive care admission [RR = 1.5 (95% CI 0.16-14.09)]; any adverse event [RR= 2.23 (95% CI 0.55-8.97)]; adverse event leading to discontinuation [RR=0.9(95% CI 0.14-5.840] were not found to favor Favipiravir. We found that in the mild to moderate category there was a reduction in the time to negative PCR [RR=1.31 (95% CI 1.03-1.68)] and duration of hospitalization by 1-3 days [Mean difference -0.9(95% CI -3.02-1.22)].

Moderate: Mortality [RR=2.56(95% CI 0.13-50.95)]; Progression to invasive mechanical ventilation [RR=0.79(95% CI 0.60-1.05)]; any adverse event [RR=1.01(95% CI 0.63-1.61)]; adverse event leading to drug discontinuation [RR = 2.56(95% CI 0.13-50.95)] were not found to favor Favipiravir or the comparison.

Severe: Data available only for Progression to invasive mechanical ventilation [RR=1.04 (95% CI 0.63-1.72)] or Critical or intensive care admission [RR=1.16 (95% CI 0.71-1.88)] were also not to favor either Favipiravir or the comparison.

In some of the studies the severity was unclear and some others it ranged from moderate to critical severity. The outcomes when analyzed in these categories of severity were not found to favor Favipiravir or the comparison.

1. All-cause Mortality:

2. Progression to Respiratory Failure

3. Progression to Oxygen Therapy

4. Progression to Invasive Mechanical Ventilation

5. Critical or Intensive Care admission for any reason

6. Duration of Hospitalization

7. Time to negative PCR

8. Time to Clinical Improvement

9. Time to Clinical Recovery

10. Adverse Events any

11. Adverse Events Serious

12. Adverse Events leading to drug discontinuation

13. Adverse events - Hyperuricemia

The Antiviral Expert Working Group met on 13th June 2021 to consider Favipiravir as a treatment for COVID-19. Conflict of interest declarations were reviewed by the Steering Committee; none were found to be relevant to Favipiravir.

A summary and then more detailed explanations of the Expert Working Group's judgements follow.

Problem

The COVID-19 pandemic in India with more than 30 million cases and over 0.39 million deaths has significantly impacted and stressed the health structure of the country. With a shortage of intensive care unit beds, oxygen and trained personnel the country is facing a major health crisis. This has prompted many irrational and experimental treatment interventions like Favipiravir in all severity of patients across the country in patients hospitalized in COVID-19 without clear indication or evidence in which subgroup of population or disease severity the drug is effective for. The group judged the problem to be of utmost priority.

Desirable effects

The panel agreed that the evidence suggests that Favipiravir doesn’t have a clinically significant effect on mortality, time to negative PCR, reducing progression of disease, duration of hospital stay or preventing critical or intensive care admissions. The expert working group (EWG) noted that the certainty of evidence for time to negative PCR was of moderate significance. However, the comparators used were different and the effect was not considered to be of great clinical significance. Panel also discussed that it possibly could reduce transmission if there was decreased time to negative PCR, however in the presence of other preventive strategies like vaccination it would probably have lower benefit and panel strongly felt that this should NOT be considered as a prevention/prophylactic method.

Undesirable effects

The pooled data did not suggest any increase in serious or other adverse events, or adverse events leading to discontinuation when Favipiravir was added to usual care or with active comparators. However, the panel felt that hyperuricemia is a well-known adverse effect of favipiravir which is self-limiting in most cases and caution should be advised for use in renal failure and gout.

Certainty of evidence

Using GRADE methodology, the evidence synthesis team rated the certainty of evidence as very low for all-cause mortality, duration of hospitalization, progression to respiratory failure, progression to oxygen therapy, progression to invasive mechanical ventilation, any adverse events and serious adverse events. Evidence was low certainty for critical or intensive care admission for any reason, adverse events leading to drug discontinuation and adverse events-hyperuricemia. There was moderate certainty of evidence for time to negative PCR. The expert working agreed with these judgements and rated the overall certainty of evidence as very low.

Values

The EWG felt that all the outcomes including those of mortality, progression to respiratory failure, oxygen therapy or mechanical ventilation, critical or intensive care for any reason, duration of hospitalisation and outcomes related to adverse events were expressed variably in the studies. However, there is probably no important uncertainty or variability on how people would value the main outcomes. The panel felt that even though a few studies reported the outcome of time to negative PCR, it is likely clinically irrelevant.

Balance of effects

The expert working group felt that the balance of effects does not favor either the intervention or the comparison. The panel felt that there is no convincing evidence to prove the benefit of this intervention. Since there were different comparators and varying severity of disease across all studies. The intervention was also found to be not efficacious as per the sensitivity analysis where results were similar when we compared after splitting into 2 categories -SOC + active comparator (another antiviral) vs together.

Resources required

The group felt that the costs were small. The erratic supply chain had led to an increased demand for this drug during the initial phase of the second wave of the pandemic despite its uncertain clinical benefits until the drug was removed from the ministry of health guidelines for COVID-19 on June 7th 2021. The group includes clinicians in different types of Indian hospitals who have a good idea of drug and hospitalization costs.

Certainty of evidence of required resources

No studies reporting this were reviewed by the group but the clinicians in the group were aware of the cost and hence felt that there was high certainty of evidence for required resources to implement this intervention.

Cost effectiveness

The panel discussed that even though there was no research evidence that evaluated cost of Favipiravir in an Indian context, it favors the comparison, as this intervention was not of clinical benefit and conferred a cost for implementation and would always be in addition to the standard care.

Equity

At this point in time this intervention would reduce equity if found efficacious (but it’s not) as cost are low and there is no need for hospitalization.

Acceptability

The group felt that this intervention is likely to have wide acceptance by all the relevant stakeholders (policy-makers, patients and clinicians) as it is an oral drug that is probably quite safe, but taking evidence and cost into account a well-informed clinician would be unlikely to use it.

Feasibility

This is a feasible intervention if found efficacious as it is easy to deliver and available easily over the counter in the country.

Currently the evidence to support using Favipiravir for the treatment of COVID-19 in any patient group is lacking, although it remains understudied and the certainty of the evidence to date is very low. Regarding adverse effects, more evidence needed to assess the clinical relevance of hyperuricemia when given as a treatment for COVID-19. It is contraindicated in pregnancy based on data from animal studies showing teratogenicity thus caution should be exercised when prescribing for patients of reproductive age. Favipiravir is an oral drug, making it suitable as an outpatient or inpatient treatment. The dose is 1800 mg twice daily on the first day, followed by 800mg twice daily up to day 14. Previously there were only 200mg and 400mg doses available making the pill burden quite high which might affect treatment adherence, however 800mg tablets are now available. A two week treatment course costs around Rs.3600. If new evidence emerges showing Favipiravir is effective and safe for the treatment of COVID-19, it should be straightforward to implement this treatment into existing protocols.

Our conditional recommendation against the use of Favipiravir applies to all subgroups of patients with COVID-19. The group considered all trials of Favipiravir, and found no subgroups where there was benefit in clinically meaningful endpoints whether evaluated by category of severity or by co morbidities. There are very limited data available assessing its use in patients with liver or kidney disease.

The recommendation against the use of Favipiravir will be reviewed as and when any new evidence emerges. Although the evidence for discontinuation of the drug because of the undesirable effects reported with widespread use such as hyperuricemia, liver dysfunction and chest pain has so far been low, this needs careful monitoring as the potential for drug-related harm cannot be ruled out.

There is currently no evidence to support the use of Favipiravir in any patient group for COVID-19 treatment. There is a need for conduct of well-structured, adequately powered randomized controlled trials with a low risk of bias to address the following:

- Is there any clinical benefit of using Favipiravir in different subgroups of disease severity or in different special populations ( children, immunosuppressed, co-morbid conditions)

- Is there a role for Favipiravir in reducing disease transmission as trials showed a mild reduction in time to PCR negativity

- Safety of the dose of Favipiravir that is required for anti-viral effect in COVID-19

- Agrawal U, Raju R, Udwadia ZF. Favipiravir: A new and emerging antiviral option in COVID-19. Med J Armed Forces India. 2020 Oct;76(4):370–6.

- Shannon A, Selisko B, Le N, Huchting J, Touret F, Piorkowski G, et al. Favipiravir strikes the SARS-CoV-2 at its Achilles heel, the RNA polymerase. bioRxiv [Internet]. 2020 May 15 [cited 2021 Jun 16]; Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7263509/

- Wang M, Cao R, Zhang L, Yang X, Liu J, Xu M, et al. Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res. 2020 Mar;30(3):269–71.

- Udwadia ZF, Singh P, Barkate H, Patil S, Rangwala S, Pendse A, et al. Efficacy and safety of favipiravir, an oral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase inhibitor, in mild-to-moderate COVID-19: A randomized, comparative, open-label, multicenter, phase 3 clinical trial. Int J Infect Dis. 2021 Feb 1;103:62–71.

- Lou Y, Liu L, Yao H, Hu X, Su J, Xu K, et al. Clinical Outcomes and Plasma Concentrations of Baloxavir Marboxil and Favipiravir in COVID-19 Patients: An Exploratory Randomized, Controlled Trial. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2021 Feb 1;157:105631.

- Chen C, Zhang Y, Huang J, Yin P, Cheng Z, Wu J, et al. Favipiravir versus Arbidol for COVID-19: A Randomized Clinical Trial. medRxiv. 2020 Apr 15;2020.03.17.20037432.

- Zhao H, Zhu Q, Zhang C, Li J, Wei M, Qin Y, et al. Tocilizumab combined with favipiravir in the treatment of COVID-19: A multicenter trial in a small sample size. Biomed Pharmacother Biomedecine Pharmacother. 2021 Jan;133:110825.

- Balykova LA, Pavelkina VF, Shmyreva NV, Pyataev NA, Selezneva NM, Shepeleva OI, et al. comparative effectiveness and safety of different schemes of ethiotropic therapy in patients with new coronavirus infection (covid-19). Pharmacy And Pharmacology. 2020 Dec 21; 8 (3): 150-9.

- Ivashchenko AA, Dmitriev KA, Vostokova NV, Azarova VN, Blinow AA, Egorova AN, et al. AVIFAVIR for Treatment of Patients with Moderate COVID-19: Interim Results of a Phase II/III Multicenter Randomized Clinical Trial. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am [Internet]. [cited 2021 Jun 14]; Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7454388/

- Ruzhentsova T, Chukhliaev P, Khavkina D, Garbuzov A, Oseshnyuk R, Soluyanova T, et al. Phase 3 Trial of Coronavir (Favipiravir) in Patients with Mild to Moderate COVID-19 [Internet]. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network; 2020 Oct [cited 2021 Jun 14]. Report No.: ID 3696907. Available from: https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3696907

- Dabbous HM, Abd-Elsalam S, El-Sayed MH, Sherief AF, Ebeid FFS, El Ghafar MSA, et al. Efficacy of favipiravir in COVID-19 treatment: a multi-center randomized study. Arch Virol. 2021 Mar;166(3):949–54.

- Dabbous HM, El-Sayed MH, El Assal G, Elghazaly H, Ebeid FFS, Sherief AF, et al. Safety and efficacy of favipiravir versus hydroxychloroquine in management of COVID-19: A randomised controlled trial. Sci Rep. 2021 Mar 31;11(1):7282.

- Solaymani-Dodaran M, Ghanei M, Bagheri M, Qazvini A, Vahedi E, Hassan Saadat S, et al. Safety and efficacy of Favipiravir in moderate to severe SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021 Jun 1;95:107522.

Covid Management Guidelines India Group - Anti-viral Working Group. Favipiravir. Covid Guidelines India; Published online on July 19, 2021; URL: https://indiacovidguidelines.org/favipiravir/ (accessed <date>).